Two of Britain’s top mountain climbers went missing on Mount Everest’s Tibetan side and are considered dead in the year 1982.

The climbers, Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker, were last seen at roughly 27,000 feet late on May 17 1982 as they prepared to ascend a second rock-and-ice pinnacle on the mountain’s unclimbed east-northeast ridge. They were never seen again once radio communication was lost.

Two days earlier, at around 26,500 feet, the sole woman on an American group making the first climb of Mount Everest’s north face was murdered. Marty Hoey, a mountain guide from Tacoma, Wash., plummeted thousands of feet into a chasm. Her body could not be found.

Both crews failed in their attempts to climb the world’s highest peak without using oxygen. Members began returning to Peking on Saturday. The leader appeared to be shaken.

Mr. Boardman and Mr. Tasker’s absence was not made public until Saturday, when the expedition’s commander, Chris Bonington, returned. He was devastated by the setback and only talked to a small number of British journalists.

Mr. Bonington stated in his report to the Chinese Mountaineering Association, a copy of which was made public, that while he looked from below via binoculars, his two red-suited comrades vanished at twilight behind the second of two large pinnacles.

Mr. Bonington, who was too fatigued to pursue them, came to the conclusion that Mr. Boardman and Mr. Tasker had fallen down the 10,000-foot Kangshung cliff, which is covered in extremely steep snow.

”It seemed unimaginable that they could have remained out of sight four nights and five days, unless some calamity occurred, particularly at that altitude, where the human body deteriorates extremely fast, especially when they were not utilizing oxygen,” Mr. Bonington wrote in his report. Four Major Climbers

Mr. Bonington’s trip consisted of just four main climbers and two support climbers, which he admitted was a ”rather tiny group” for such a large peak.

Dick Renshaw, one of the major climbers, had been evacuated due to stroke symptoms produced by high altitude, leaving Mr. Boardman and Mr. Tasker to lead the main attack, with Mr. Bonington, 47, and Adrian Gordon, a support climber, assisting them.

”All of us expressed while we were doing the climb that it was the most arduous climb any of us had ever undertaken, but it was a worthwhile exciting challenge and Pete and Joe were very nearly in sight of complete success, and it’s just tragic that this happened to them,” said Mr. Bonington, who led a successful ascent of Everest from Nepal in 1975.

Mr. Boardman and Mr. Tasker’s disappearance is reminiscent of a mystery that happened in 1924 when two members of a British expedition, George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, vanished after being sighted fewer than 1,000 feet from the summit. For over a half-century, people have speculated about whether they finished the ascent before being slain. Mount Everest was not ascended officially until 1953.

Mr. Boardman, who was 31 and married at the time, climbed Mount Everest on the British assault of the southwest face from Nepal in 1975 and Kanchenjunga, the world’s third highest peak, without oxygen in 1979. After the deaths of its two former directors in mountain accidents, he took over as director of the International School of Mountaineering in Leysin, Switzerland. Author of a Contemporary Classic.

Mr. Tasker, 33 and unmarried, had an exceptional climbing resume. He made the first British winter ascent of the Eiger’s north face in Switzerland, and he also climbed Kanchenjunga without oxygen.

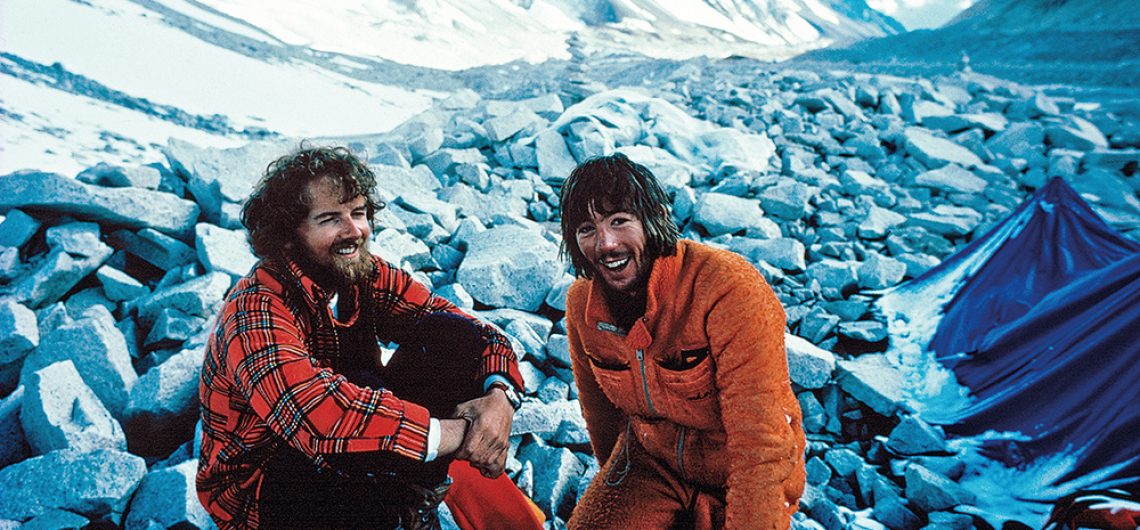

Both climbers were perhaps best known for their two-man ascent of the sheer west wall of India’s 22,520-foot Changabang peak. ”The Shining Mountain,” Mr. Boardman’s prize-winning book describing their ascent, has become a contemporary classic in mountaineering literature.

Last summer, Mr. Boardman and Mr. Tasker joined Mr. Bonington on the first ascent of Mount Kongur in the Chinese Pamirs.

”They both possessed great mountain judgment and, although bold and resolute in idea, were also prudently cautious,” Mr. Bonington said in his report to the Chinese. ”Their loss is enormous to the entire climbing world.”

On their four unsuccessful attempts to reach the summit from their advance camp at about 26,600 feet, the Seattle-based American climbers, led by Lou Whittaker, encountered strong winds, freezing temperatures, and blizzards. Miss Hoey is said to have died during the second assault on the summit. Frostbite turned back

Larry Nielson of the American team climbed solo to roughly 27,500 feet on the third attempt before returning due to severe frostbite. He needed to be dragged down the mountain.

A fourth attack was called off due to avalanches.

An American team from San Francisco gave up after reaching 22,000 feet due to severe weather last October. Next spring, another American team will attempt to ascend Mount Everest through Tibet. American climbers have reached Everest’s summit from Nepal but not from Tibet.

Because it has the world’s highest unclimbed mountains and some virtually unexplored alpine terrain, China has become the latest mecca for expedition mountaineers. Ascents of Everest are planned for next year by teams from Japan, Italy, Spain, and Chile.

Who was Peter Boardman?

Peter Boardman (25 December 1950 – 17 May 1982) was a climber and novelist from England. He is most known for a series of daring and lightweight Himalayan treks, typically in collaboration with Joe Tasker, as well as his contribution to mountain writing. Boardman and Tasker perished on Mount Everest’s North East Ridge in 1982. In their honor, the Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature was founded.

Death on Everest

Boardman’s death was reported in the media and transmitted to Hilary Boardman in Leysin and Dorothy Boardman in Manchester.On July 11, 1982, a memorial service was conducted at St George’s Church in Stockport. Hilary Boardman and Maria Coffey, Joe Tasker’s girlfriend, traveled to the north side of Everest as far as Advance Base Camp in September 1982 to recreate Boardman and Tasker’s previous trek.

Discovery of Peter Boardman’s Body

Boardman and Tasker’s high point was not reached on expeditions to the North East Ridge in 1985, 1986, or 1987. Russell Brice and Harry Taylor crossed the Pinnacles in August 1988, completing the unclimbed segment of the route before descending down the North Ridge.

Due to the thick monsoon snow cover, they observed no indication of Boardman or Tasker.

In 1992, a combined Japanese-Kazakh expedition crossed the Pinnacles but was unable to proceed to the top. They discovered a body beyond the second pinnacle on the Rongbuk side of the ridge at roughly 8,200m. Photographs obtained by Vladimir Suviga and transmitted to Chris Bonington allowed the body to be recognized as Peter Boardman based on his attire and characteristics.

A Japanese expedition scaled the whole ridge in 1995. They also discovered a corpse that was first considered to be Joe Tasker’s. Chris Bonington concluded that both sightings were of Boardman after re-examining all of the evidence: “At first it was assumed that this was Joe Tasker, but after carefully comparing the written descriptions and photographs provided by each expedition, I became convinced that this was the same as the original sighting and thus that of Pete.”

Book Writer

The Shining Mountain, Boardman’s book on the 1976 Changabang trip, is considered one of the best works of mountain literature and was awarded the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize for Literature in 1979. A second book, Sacred Summits, was released posthumously, chronicling his climbing efforts on Carstensz Pyramid, Kangchenjunga, and Gauri Sankar in 1979.

These volumes, together with those of Joe Tasker, were reprinted in the Boardman Tasker Omnibus in 1995.

Who was Joe Tasker?

Joe studied at Ushaw Seminary in County Durham from the age of 13 to 20 in order to become a Catholic priest. Fascinated by Jack Olsen’s book The scale Up to Hell, which recounted terrifying accounts of catastrophic efforts to scale the North Face of the Eiger, he began climbing in a nearby quarry in 1966.

He worked as a dustman after leaving the seminary before studying sociology at Manchester University, where he was an active member of the Student Union’s gypsy liaison and soup-run clubs. During this time, he improved his climbing abilities, progressing from rock climbing in the UK to more difficult routes in the Alps.

Mountain Climbing Adventures

Dick Renshaw, whom Tasker met at university, was Tasker’s first regular climbing companion. In the winter of 1975, they climbed the North Face of the Eiger. Later that year, the first ascent of the South-East ridge of Dunagiri (7066m) in the Garhwal Himalayas occurred. They were lucky to live after running out of food and fuel on the descent, albeit Renshaw got frostbite in his fingers.

His 1976 climb of the West Face of Changabang (6864m), which bordered Dunagiri, was his first collaboration with Peter Boardman and was widely regarded as a daring, brilliant accomplishment of mountaineering.

Tasker attempted Nuptse with Doug Scott and Mike Covington in the autumn of 1977, and he and Boardman were invited to Chris Bonington’s K2 trip in 1978, which was abandoned when Nick Estcourt was killed in an avalanche.

In 1979, a small team led by Tasker, Boardman, and Doug Scott climbed Kangchenjunga (the third highest mountain in the world at 8,598 meters) via a new route from the north-west (Georges Bettembourg was also on the team but did not reach the summit); this was also the first ascent of the mountain without the use of supplemental oxygen. Tasker’s second attempt on K2 in 1980 was nearly wiped out by an avalanche and eventually failed.

In the winter of 1980-1981, Tasker was part of an eight-man team (along with Alan Rouse, John Porter, Brian Hall, Adrian Burgess, Alan Burgess, Pete Thexton, and Paul Nunn) attempting a difficult winter assault on Mount Everest’s West Face; this failed but was recounted in Tasker’s first book Everest the Cruel Way.

Tasker met Maria Coffey in 1980, the girlfriend who would write about her grief after his death in her book Fragile Edge. He was a member of the British team who made the first ascent of Kongur Tagh (7,649 m) in China in 1981, together with Chris Bonington, Peter Boardman, and Alan Rouse.

He and Boardman vanished on the North-East Ridge of Everest on May 17, 1982. Boardman’s body was discovered in 1992, resting in a sitting position just past the second pinnacle in the extremely difficult area of the “Three Pinnacles” on Everest’s middle North-East Ridge, but Tasker’s body is still missing, though some of his climbing equipment was discovered between the second and third pinnacles.

On the night of his departure for the British Everest expedition in 1982, Tasker had handed his manuscript for his second book, Savage Arena, which described his climbing life from the 1960s to 1980. Later that year, the book was published posthumously.

The Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature was established in 1983 in commemoration of Tasker and Boardman.

The Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature

The Boardman Tasker Charitable Trust, founded in 1983 to honor the lives of Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker, honors their legacy by presenting the yearly Award for Mountain Literature and the Lifetime Achievement Award.

The Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Writing is a £3,000 award given annually by the Boardman Tasker Charitable Trust to an author or writers for “an original work that has made an outstanding contribution to mountain literature.” After their deaths on Mount Everest’s northeast ridge in 1982, British climbers Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker, both of whom published books about their climbing exploits, founded the award in 1983.

It can be given for a work of fiction or nonfiction, poetry or drama, but it must be written in (or translated into) English. The award is given out at the annual Kendal Mountain Festival.

The Boardman Tasker Prize Winners

- 2022 Brian Hall, High Risk: Climbing to Extinction and Helen Mort, A Line Above the Sky: A Story of Mountains and Motherhood

- 2021 David Smart, Emilio Comici: Angel of the Dolomites

- 2020 Jessica J. Lee, Two Trees Make a Forest: On Memory, Migration and Taiwan

- 2019 Kate Harris, Lands of Lost Borders: A Journey on the Silk Road

- 2018 David Roberts, Limits of the Known

- 2017 Bernadette McDonald, Art of Freedom: The Life and Climbs of Voytek Kurtyka

- 2016 Simon McCartney, The Bond: Two Epic Climbs in Alaska and a Lifetime’s Connection Between Climbers

- 2015 Barry Blanchard, The Calling: A Life Rocked by Mountains

- 2014 Jules Lines, Tears of the Dawn

- 2013 Harriet Tuckey, Everest – The First Ascent: The Untold Story of Griffith Pugh, the Man Who Made It Possible

- 2012 Andy Kirkpatrick, Cold Wars: Climbing the Fine Line between Risk and Reality

- 2011 Bernadette McDonald, Freedom Climbers

- 2010 Ron Fawcett with Ed Douglas, Ron Fawcett, Rock Athlete

- 2009 Steve House, Beyond the Mountain

- 2008 Andy Kirkpatrick, Psychovertical

- 2007 Robert Macfarlane, The Wild Places

- 2006 Charles Lind, An Afterclap of Fate: Mallory on Everest

- 2005 Andy Cave, Learning to Breathe

- 2005 Jim Perrin, The Villain: The Life of Don Whillans

- 2004 Trevor Braham, When the Alps Cast Their Spell

- 2003 Simon Mawer, The Fall

- 2002 Robert Roper, Fatal Mountaineer

- 2001 Roger Hubank, Hazard’s Way

- 2000 Peter Gillman and Leni Gillman, The Wildest Dream: Mallory – His Life and Conflicting Passions

- 1999 Paul Pritchard, The Totem Pole: And a Whole New Adventure

- 1998 Peter Steele, Eric Shipton: Everest and Beyond

- 1997 Paul Pritchard, Deep Play: A Climber’s Odyssey from Llanberis to the Big Walls

- 1996 Audrey Salkeld, A Portrait of Leni Riefenstahl

- 1995 Alan Hankinson, Geoffrey Winthrop Young: Poet, Mountaineer, Educator

- 1994 Dermot Somers, At the Rising of the Moon

- 1993 Jeff Long, The Ascent

- 1992 Will McLewin, In Monte Viso’s Horizon: Climbing All the Alpine 4000m Peaks

- 1991 Alison Fell, Mer de Glace

- 1991 Dave Brown and Ian Mitchell, A View from the Ridge

- 1990 Victor Saunders, Elusive Summits

- 1989 M. John Harrison, Climbers

- 1988 Joe Simpson, Touching the Void

- 1987 Roger Mear and Robert Swan, In the Footsteps of Scott

- 1986 Stephen Venables, Painted Mountains: Two Expeditions to Kashmir

- 1985 Jim Perrin, Menlove: The Life of John Menlove Edwards

- 1984 Linda Gill, Living High: A Family Trek in the Himalayas

- 1984 Doug Scott and Alex MacIntyre, The Shishapangma Expedition

![]()

Comments