The first ascent of Mount Kenya, the second highest mountain in Africa is attributed to Halford Mackinder (1861–1947), who was very well industrious in school during the Edwardian era, also commonly known as the “father of modern British geography.” But he was also famous in his time for being the first person to successfully climb Mount Kenya. It took him three months of hard work, but he reached the top of this huge African mountain. In fact, this accomplishment is still hotly discussed among biographers of the person because of the strange events that led to its happy ending.

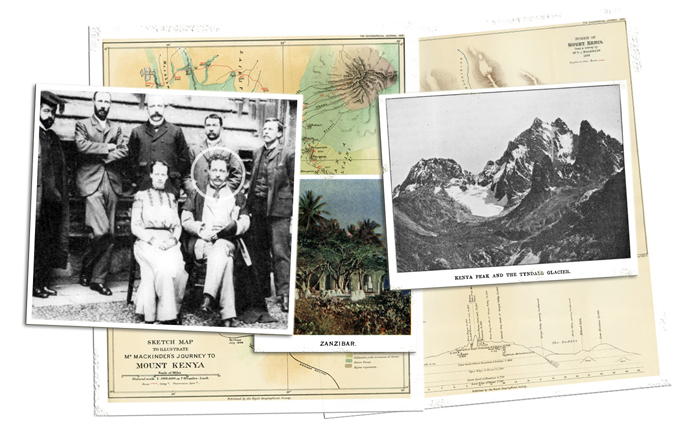

About 150 kilometres northeast of Nairobi is Mount Kenya, which is the second-highest mountain in Africa after Kilimanjaro. It is more than 5,000 metres high and has 11 small glaciers on top of its peak. In 1849, German missionary Johann Ludwig Krapf was the first person from Europe to see it. He was exploring the area to find the source of the White Nile. Thirty-four years later, a British mission led by Joseph Thomson tried to climb the mountain but failed because the Kikuyu tribes in the area were hostile. This disappointing outcome did not happen again in 1887, when a second mission led by the handsome Hungarian Count Samuel Teleki reached an elevation of about 4,350 metres on the southwest slopes and gathered useful information about the plants and animals that lived there. But European explorers didn’t reach the peak until the summer of 1899, when Mackinder and his team arrived in Mombasa with the clear goal of climbing Mount Kenya for political and scientific reasons. In fact, the expedition was probably meant to make a political statement against the rise of German power in East Africa at the time. The goal was to boost British imperial prestige in this important part of the sea route to India. At the same time, Mackinder wanted to use his own success to help British geography by convincing the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) that his teaching projects at Oxford were good ideas.

About 150 kilometres northeast of Nairobi is Mount Kenya, which is the second-highest mountain in Africa after Kilimanjaro. It is more than 5,000 metres high and has 11 small glaciers on top of its peak. In 1849, German missionary Johann Ludwig Krapf was the first person from Europe to see it. He was exploring the area to find the source of the White Nile. Thirty-four years later, a British mission led by Joseph Thomson tried to climb the mountain but failed because the Kikuyu tribes in the area were hostile. This disappointing outcome did not happen again in 1887, when a second mission led by the handsome Hungarian Count Samuel Teleki reached an elevation of about 4,350 metres on the southwest slopes and gathered useful information about the plants and animals that lived there. But European explorers didn’t reach the peak until the summer of 1899, when Mackinder and his team arrived in Mombasa with the clear goal of climbing Mount Kenya for political and scientific reasons. In fact, the expedition was probably meant to make a political statement against the rise of German power in East Africa at the time. The goal was to boost British imperial prestige in this important part of the sea route to India. At the same time, Mackinder wanted to use his own success to help British geography by convincing the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) that his teaching projects at Oxford were good ideas.

Aside from Mackinder, the chief leaders of the mission were Canadian doctor Sidney Hinde, who had done some exploring in the Congo before, and fine photographer Campbell B. Hausburg, who had also helped pay for the trip. There were also two collectors chosen by the Natural History Museum of London and two French alpine guides with a lot of experience climbing similar Alpine hills. When Mackinder and his group got to Mombasa, they ran into big problems: the coastal area of Kenya was actually going through a famine, and at first, the British government wouldn’t give the mission any of the important supplies they needed. Through his ties to the RGS, Mackinder was able to get enough food for his trip, but the fact that British officials weren’t giving him any real help made everyone in the group very nervous. It was clear that this would lead to big problems in the coming weeks.

After hiring some Swahili porters in Nairobi, the group started their march north in early August. They were constantly bargaining with Masai and Wakikuyu chiefs to get permission to cross their lands. Hinde, who had been in the Belgian war against the Congo Arabs, had very strict rules for the porters and would whip them for small offences. Mackinder never seemed to question this harsh treatment of African people. He called the Swahilis “faithful dogs” and “poor devils” in his diary, while the Masais are usually admired for their martial skills. This original ambivalence became more noticeable in the middle of the expedition, when the small amounts of food that had been brought from Mombasa and Nairobi started to run out and there was nowhere else to find food. Because they were hungry, some porters tried to leave the party, but Hausburg’s sudden show of guns stopped them. Then Mackinder decided to break up the party and sent Hausburg towards Lake Navaisha to find food. It was a dramatic race against time that ended with eight servants being brutally shot for leaving the party or not following orders. The event is still being discussed by scholars; there isn’t a lot of solid proof to back up what happened, so people are just guessing about what happened and who was responsible for the massacre. It’s true that both Hausburg and Mackinder didn’t care about people when they were working on their big African project. They were just stuck in the racist ideas of their time. Because of this, the journey to Mount Kenya perfectly captures the violent, greedy, and mentally obsessed spirit of European imperialism at the end of the 1800s. A dangerous mix that Joseph Conrad beautifully described in his great book Heart of Darkness, which came out later as part of a worldwide movement against Belgian crimes in the Congo.

Once they had enough food, in late August, Mackinder and the two French guides started the real climb up the mountain, setting up their first field base in the Hohnel Valley. Then, after several failed efforts to cross the Darwin Glacier, the three men finally made it to the top of the peak at noon on September 13. They looked down at the snowy ground and collected important scientific samples. It was a huge relief for Mackinder to finally reach his goal, and his notebook is full of happy entries like “The peaks were again clear.” Kenya is such a beautiful mountain range. It’s very lovely and not harsh, but its beauty makes me think of a cold woman.

But the happiness didn’t last long. Six days later, the return trip began through the Aberdare Range, and there were new problems with the African porters that had to be fixed by violence and threats. When the trip got to Lake Navaisha at the end of the month, Mackinder left the group right away to go back to Britain for school duties at Oxford. At the same time, a short telegram told the geographical community, which was meeting in Berlin for an international congress, that the trip had been a success. According to Hans Meyer, a German climber, this was a “slap” in the face to the host country, since Meyer planned to climb Mount Kenya in the near future. It also shows how arrogant Mackinder’s trip to East Africa was. The RGS was proud of the success of one of its young members, so it helped to open an independent School of Geography in Oxford. This school quickly became a recognised educational institution that spread the new field of geography across the country. Mackinder tried to use his newfound fame as an explorer to get into politics by running as a Liberal in the Leamington district during the Khaki election of 1900. However, his Conservative opponent, Alfred Lyttelton, easily beat him. Once he joined the Tories in the summer of 1903, he didn’t become an MP for ten years.

The notebooks and diaries of the Mount Kenya trip were supposed to be put together in one book for Heinemann, but Mackinder broke the agreement he made with such a well-known publisher. Some scholars have recently made a lot of assumptions about this editing mistake. For example, Gerry Kearns thinks that Mackinder didn’t write a full review of the Mount Kenya ascent to hide the fact that he was responsible for mistreating and killing African porters. K.M. Barbour disagrees with this claim, pointing out that Mackinder had a lot of personal problems in the early 1900s. In fact, the trip to Africa hurt his marriage to Emilie “Bonnie” Ginsburg more than it helped. They divorced painfully in late 1900. Mackinder was so upset by this failure that he threw himself into his political and educational tasks. He spent days and nights writing long essays or talking with friends in a number of dining clubs. He forgot about his promise to Heinemann, which made his notes on the trip very hard to understand. Emilie and he were permanently split up, and the married couple didn’t get back together fully until the late 1930s.

Before the end of World War I, no one had done as well in East Africa as Mackinder. That is, until other British explorers reached the top of Mount Kenya, opening up new ways to study its beautiful glaciers. Eric Shipton was probably the most impressive of them all. He climbed the mountain in January 1929 and then helped to start the Mountain Club of East Africa that same year. During World War II, three Italian prisoners of war quickly surpassed his heroics when they escaped from their Nanyuki concentration camp by climbing the third peak of the mountain on their doomed escape. The three soldiers were so hungry and thirsty that they later chose to return to their original prison, where they were given only 28 days of solitary confinement as a reward for their bravery. Felice Benuzzi, who was their leader, wrote a popular account of this journey in 1946. It was called No Picnic on Mount Kenya, which is a very appropriate title. People still think of it as a classic in the mountaineering field. In 1994, director Donald Shebib turned it into a movie called The Ascent, which starred Ben Cross and Vincent Spano.

Right now Mount Kenya is a great national park that has been a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve since 1978. People have been worried lately about how its major glaciers are melting, which may be because of the bad effects of climate change. Still, hundreds of alpinists and naturalists visit the spot every year because of the beautiful scenery and wide range of plants and animals that live in this part of Africa. There are leopards, antelopes, porcupines, elephants, lions, and a rare species of owls called Bubo capensis mackinderi. It was named after Halford Mackinder, who was the first person to climb Mount Kenya in 1899 and will never be forgotten.

The first ascent of Mount Kenya is credited to Halford John Mackinder, an English geographer, and his companions Cesar Ollier and Joseph Brocherel. This historic expedition took place in 1899, marking a significant milestone in mountaineering history.

Mount Kenya, located around 150 kilometers northeast of Nairobi, is the second highest peak on the African continent after Kilimanjaro. Its highest peaks, Batian, Nelion, and Point Lenana, were named by Mackinder after Maasai laibons, who were spiritual leaders at the top of the social hierarchy.

The expedition faced numerous challenges, including navigating through dense forests, rugged terrain, and adverse weather conditions. Mackinder and his team embarked on the ascent from the Nanyuki side, known today as the Sirimon route. Despite the obstacles, they successfully reached the summit of Point Lenana, which stands at 4,985 meters above sea level.

Mackinder’s expedition to Mount Kenya was not without controversy and hardship. The journey was fraught with difficulties, including shortages of food and supplies, conflicts with local porters, and even violence. Mackinder’s handling of these challenges has been the subject of debate among historians and scholars.

Nevertheless, Mackinder’s achievement in ascending Mount Kenya was a significant accomplishment in the exploration of East Africa. His expedition paved the way for future climbers and adventurers to explore the majestic peaks of Mount Kenya, which today attracts visitors from around the world.

Mount Kenya has since become a renowned national park, designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1978. Despite concerns about the retreat of its glaciers due to climate change, the park continues to attract visitors interested in its stunning scenery and diverse wildlife.

The legacy of Mackinder’s expedition lives on in the annals of mountaineering history, commemorated by the peaks named after Maasai leaders and the enduring allure of Mount Kenya as a destination for adventure and exploration

![]()

Comments