Imagine running a marathon after climbing Africa’s highest peak and lugging an extra 120 pounds the entire way.

Breathing is tough. Your joints throb with pain. Everything is in pain.

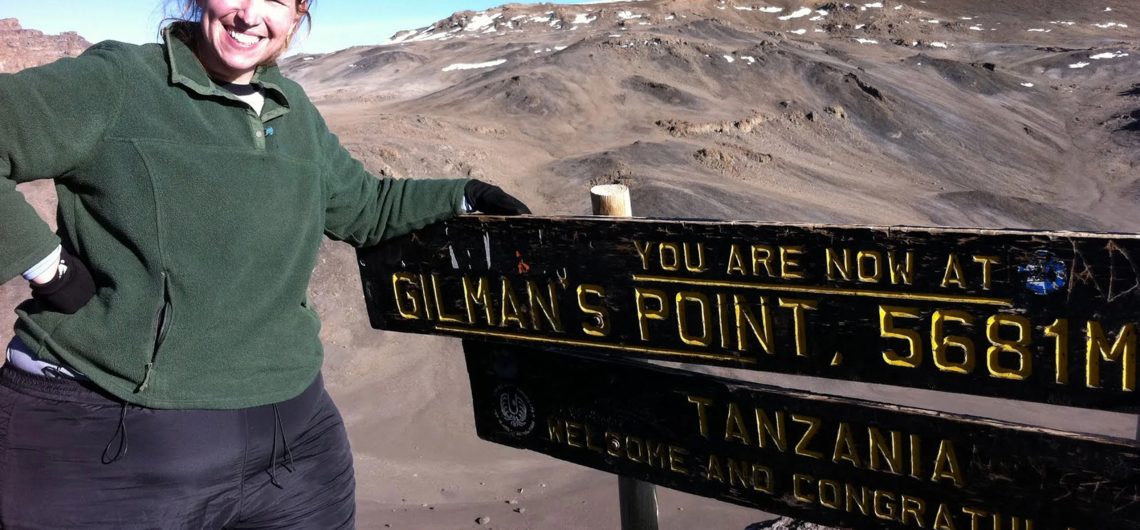

That’s how Kara Richardson Whitely felt after descending Mount Kilimanjaro twice, despite weighing more than 300 pounds each time.

That’s correct. She has twice reached the peak of the world’s highest freestanding mountain.

Whitely decided to start working through her longstanding eating issues during her third ascent.

“If you’re going through a shift, Kilimanjaro is a terrific spot to cycle through things in your thoughts because there is so much time spent with oneself,” she added.

She’s struggled with her weight since she was nine years old, around the time her parents separated and her father vanished.

Whitely was then sexually raped by a friend of her elder brother on her 12th birthday. “My weight surged past the 300-pound threshold” in college as food became an emotional crutch.

Throughout her 20s and 30s, Whitely struggled with her weight, but she dreamed of going on big adventures and trekking the world’s tallest mountains.

She remarked, “There weren’t a lot of hikers that looked like me.” Whitely and her husband, Chris, summited Mount Kilimanjaro in 2007, following a spectacular 120-pound weight reduction.

After two years, one baby, and a weight gain of roughly 300 pounds, Whitely attempted a second ascent of the mountain, which he failed to complete.

Whitely trained for the climb in 2011, but she made it on her third attempt without attempting to drop weight.

Gorge: My Journey Up Kilimanjaro at 300 Pounds was released in April 2015 by Whitely. She finished the novel while attending Butler University’s Chamonix Summer Writing Program in the French Alps, where she collaborated with Wild author Cheryl Strayed.

Whitely has featured on Oprah’s Lifeclass, Good Morning America, and a Weight Watchers blog since her initial ascent.

She now travels the country as a mother of three children, ages 8, 3, and 9 weeks, giving motivational lectures at colleges and corporations such as Google about adventure, overcoming challenges, fitness, eating disorders, body acceptance, and other topics. Her next novel, tentatively titled The Family Plot, is set to be published in spring 2017.

Question: How did you get the idea to climb Kilimanjaro?

Answer: When I was at my heaviest, 360 pounds, before my initial weight reduction, the highest thing I could hike was a stairwell, and even that gave me a run for my money.

I’d get these adventure catalogs in the mail and, while being quite sedentary at the time, I’d fantasize about visiting those destinations — Machu Picchu, The Alps, or Kilimanjaro — while eating a king-size Kit Kat bar.

After losing 120 pounds, I felt like I was on top of the world on my first trek up Kilimanjaro. After that, I had another experience, which was having a kid, as soon as I went down the mountain.

I gained 70 pounds, just like a lot of others who struggle with their weight. I was in a terrible situation.

I attempted to climb the mountain around two years later, but I failed miserably because I failed to undertake the necessary training and commit the necessary time to myself in order to prepare for the climb.

Q. What prompted you to give it a third shot?

A. I didn’t feel like I could climb mountains, walk or do anything else after that second effort.

Then there were a few friends and a relative who wanted to climb the mountain to raise money for the Global Alliance for Africa. So we were putting all of this money on the line, roughly $25,000, for this charity that I was passionate about.

Even though I was having serious self-esteem issues, I decided to give it one more shot.

This time, though, things were different. I wasn’t thinking of it as a way to lose weight.

I wanted to appreciate where I was at, which was about 300 pounds, and then progress from there. That was a completely different perspective on my weight loss journey than I’d ever had before.

Q. How do you know that?

A.: Because I used to say things like, “I don’t like how I look, therefore I’m going to go on a diet and do this detox because I’m eating garbage.”

It was a far more unpleasant debate than opting to keep doing what I was doing and not try to lose weight miraculously. Because I knew I would fail if I decided to do it.

As a result, I needed to find a trainer who didn’t regard me as a before-and-after comparison.

I worked out pretty hard, but I didn’t do it in such a manner that I was putting my body at risk, so that’s where the true healing took place. Of course, I gained and lost a few pounds along the way, but I climbed the mountain as only I could.

Q. It appears that the mental hurdles were just as difficult as the physical ones.

A. You run out of things to say to your fellow climbers when you embark on a trek as big as Kilimanjaro and do that much walking. As a result, you spend a lot of time thinking.

There are several diversions in life. I’m usually staring at something, whether it’s my phone, a TV, a computer screen, or anything else.

On the other hand, on a mountain, it’s just you and the mountain. You can only move forward by putting one foot in front of the other.

When I did this climb, I decided that not only was I going to love myself and go from there, but I was also going to figure out the root and reason why I used food as a crutch for so many years, not just the narrative of my father leaving and how much I loved and missed him throughout my life, and also how I was sexually assaulted on my 12th birthday, but how that translates into everyday life when I’m lonely because my husband is out doing something and I go into abandonment.

That’s when I turn to food — when I’m suddenly alone and the only way to calm my racing heartbeat or whatever else is on my mind is to eat.

Q. When did you realize you could write a book on your experiences on the third climb?

A. I was already a published author, having self-published a book on my first climb called Fat Woman on the Mountain. With the third climb, however, I felt compelled to write honestly and bravely about not only my Kilimanjaro trip, but also my eating difficulties, because I knew that so many other people were going through the same thing.

Food no longer has the same power over me now that I’ve written about my food difficulties and laid it all out on the table, so to speak, since the trouble with my eating in the past was that I did so much of it in secret.

In fact, there was no such thing as a secret. I had gained weight, as you could tell.

However, I’d have a half-gallon of ice cream before replacing it. That’s when I realize I’m in serious trouble.

I’m becoming healthier the more I talk about it and share my experience.

Q. How will you communicate to your three young children about weight and body acceptance as a mother of three?

A. That’s a large part of what I’m writing about in my next book, which is primarily about my community garden in our town and has the working title The Family Plot. But there’s a lot more to it than that.

There’s a lot to this ongoing balancing act of your personal weight concerns with your desire to avoid passing them on to your children. But, because children are children, they want to consume sweets and other treats.

How can you live a healthy life for yourself and then for your family? It’s a constantly changing and flowing subject.

I try to avoid using the term “fat” as a descriptor. It is only a description.

I’m a bigger hiker, but that’s not the most essential thing. I’m an ambassador for the American Hiking Society because there are a lot of folks my size who want to hit the trails.

Q. Children’s comments about your appearance are one thing, but how do you handle adult comments?

A. I’m not always good at dealing with it. I’m human, and I’m still terrified of bullies.

I’ve had my fair share of them.

On the mountain, when the porters were betting against me, I had the most crucial experience, which I wrote about in Gorge.

There’s a sequence when I explain how I found out about this. I could hear them all laughing and using my name the night before the climb — they nicknamed me “mama kubwa”, which is Swahili for “big lady,” and they kept saying it over and again.

When I questioned the guide, I discovered that they had decided to gamble against me on the mountain.

“Did you make a money bet?” I inquired of the head guide. “You should,” she adds. You should put your money on me.” That was one of the few occasions I made a successful comeback.

Q: What do you hope others will take away from your experience?

A. The most essential aspect of my trip has been learning to appreciate where I am and where I want to go from there. To keep going ahead is crucial in my life.

Gorge is essentially about this. Begin with loving yourself, and work your way up from there.

Q. Do you have any plans for forthcoming adventures?

A. I’d want to go hiking in New York’s Adirondack Park.

I’d want to go trekking in Hawaii as soon as possible. Machu Picchu, of course, is still on my bucket list.

Source: Kara Richardson Whitley

![]()

Comments